If there is one thing I want to tell people, it’s this: it’s okay to ask.

I was so happy when Gillette Children’s Hospital published a book with that title a few years ago, and I’ve since shared it at storytime a couple of times with good results. Most recently, I read it in the context of friendship stories. “Sometimes our friends are different from us,” I said before I opened the book, “and it’s okay to talk about what makes us different and the same.” A simple message for the storytime crowd.

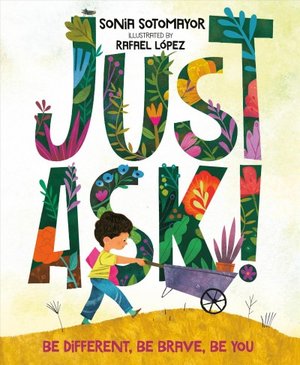

But for those of you who are looking for something with a bit more content with the same message, I might recommend Just Ask!: Be Different, Be Brave, Be You by Sonia Sotomayor. Yes, that Sonia Sotomayor. It turns out she agrees with me. The things that make us different don’t have to be hushed up or hidden. We can celebrate our differences even as we come together as friends. The book features children with various disabilities and differences talking about themselves while the illustrations by Rafael López (one of my absolute favorite illustrators, I might note) show children planting a community garden together. It’s bright, beautiful, and positive. There is so much to love here.

But for those of you who are looking for something with a bit more content with the same message, I might recommend Just Ask!: Be Different, Be Brave, Be You by Sonia Sotomayor. Yes, that Sonia Sotomayor. It turns out she agrees with me. The things that make us different don’t have to be hushed up or hidden. We can celebrate our differences even as we come together as friends. The book features children with various disabilities and differences talking about themselves while the illustrations by Rafael López (one of my absolute favorite illustrators, I might note) show children planting a community garden together. It’s bright, beautiful, and positive. There is so much to love here.

I want everyone to read books like these with their kids. Let’s talk about who we are—all the parts of out identities. Let’s ask questions of the people in our world to get to know their experiences.

Let’s also ask questions of this book itself. Why doesn’t Just Ask! use the word “disability”? To me, it feels like by using a euphemism like “differently abled” the book is talking around the identities of the people it features, which is seemingly the opposite of the book’s intent. I don’t believe that disabled is a bad word, and I would argue that there’s no reason to avoid using it. It’s complicated, I know. Identity can be complicated, but it’s worth asking the question here.

See this post from The Conscious Kid for their thoughts.

Ultimately, recommended with caution.

I recently finished reading Wonder by R.J. Palacio aloud to my daughter, which might seem like a surprising choice to some since the book is, arguably, inspiration porn that perpetuates the idea that the people who look significantly different deserve accolades for simply existing and anyone who befriends such a person is a hero.

I recently finished reading Wonder by R.J. Palacio aloud to my daughter, which might seem like a surprising choice to some since the book is, arguably, inspiration porn that perpetuates the idea that the people who look significantly different deserve accolades for simply existing and anyone who befriends such a person is a hero.

I wish I had a cool story like the girl in

I wish I had a cool story like the girl in