It seems to be a general rule that every story in which an amputee character gets any page time at all will also feature a crocodile. Or maybe a shark or a tiger. It doesn’t matter what wild animal one chooses, and it doesn’t matter what the truth of the story is. What matters is surprising people.

No one expects much from a less than fully limbed person, and I can speak from personal experience when I say that it can be rather draining to live a life in which people don’t expect you to be able to tie your own shoes or do much of anything for yourself. I surprise people on a near daily basis by my ability to accomplish the most basic of tasks. In a world of such constant underestimation, there is an almost irresistible pull to really surprise people, to shock them into considering their assumptions, to change the story they’ve told themselves. That’s where the wild animals come in. No one ever expects a crocodile.

While it is perhaps something of a cliche for an amputee character to make up some wild story about their limb loss, I can’t deny that it happens. I laughed when I read the scene in A Time to Dance when Veda responds to rude people with a crocodile story. I’d have done much the same if I were her. I did much the same many times as a teen. I am, and always have been, happy to answer questions asked kindly, but there was a time in my youth when rude questions, comments, or staring were almost certainly answered rudely or with a crocodile story intended to shut down the conversation by surprising people.

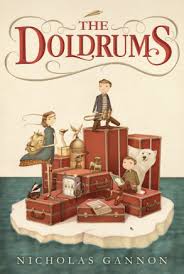

In The Doldrums, Adelaide tells a crocodile story with the words “chewed it clean off” when a man stares at her prosthetic leg. The man is so surprised he leaves the cafe without his coffee. Later she finds that the story works initially with the other kids at her new school, but it quickly gets out of hand. A word of advice: if your goal is to shut down the conversation, a crocodile story will only work with adults. Kids will just be more interested and probably call you “crocodile girl.” That is exactly what happens to Adelaide. It isn’t exactly a winning strategy for getting people to leave you alone, and it definitely won’t make you any friends.

story with the words “chewed it clean off” when a man stares at her prosthetic leg. The man is so surprised he leaves the cafe without his coffee. Later she finds that the story works initially with the other kids at her new school, but it quickly gets out of hand. A word of advice: if your goal is to shut down the conversation, a crocodile story will only work with adults. Kids will just be more interested and probably call you “crocodile girl.” That is exactly what happens to Adelaide. It isn’t exactly a winning strategy for getting people to leave you alone, and it definitely won’t make you any friends.

However, I have found that it is often the people who don’t react quite like everyone else who make the best of friends. Adelaide’s crocodile story makes Archer, a wannabe adventurer, jealous. “It’s an odd thing to be jealous of a girl whose leg was eaten by a crocodile. Few people would be jealous of that. But Archer was few people. And it wasn’t so much the loss of a limb as it was the entire story.” That, of course, is the beginning of a real friendship, or at least, it becomes a real friendship when they eventually get past Adelaide’s story and Archer’s jealousy.

It has been a very long time since I told a crocodile story about myself. These days I am much more focused on keeping the conversation open, but there are times when I am tempted. Especially considering the real story of my limb difference is so boring. Of course, I’ve learned that the boring story is the most unexpected of all. The truth is, I’ve gotten so much more surprise from “I was born this way” than I ever did from any wild animal story I told as a kid.